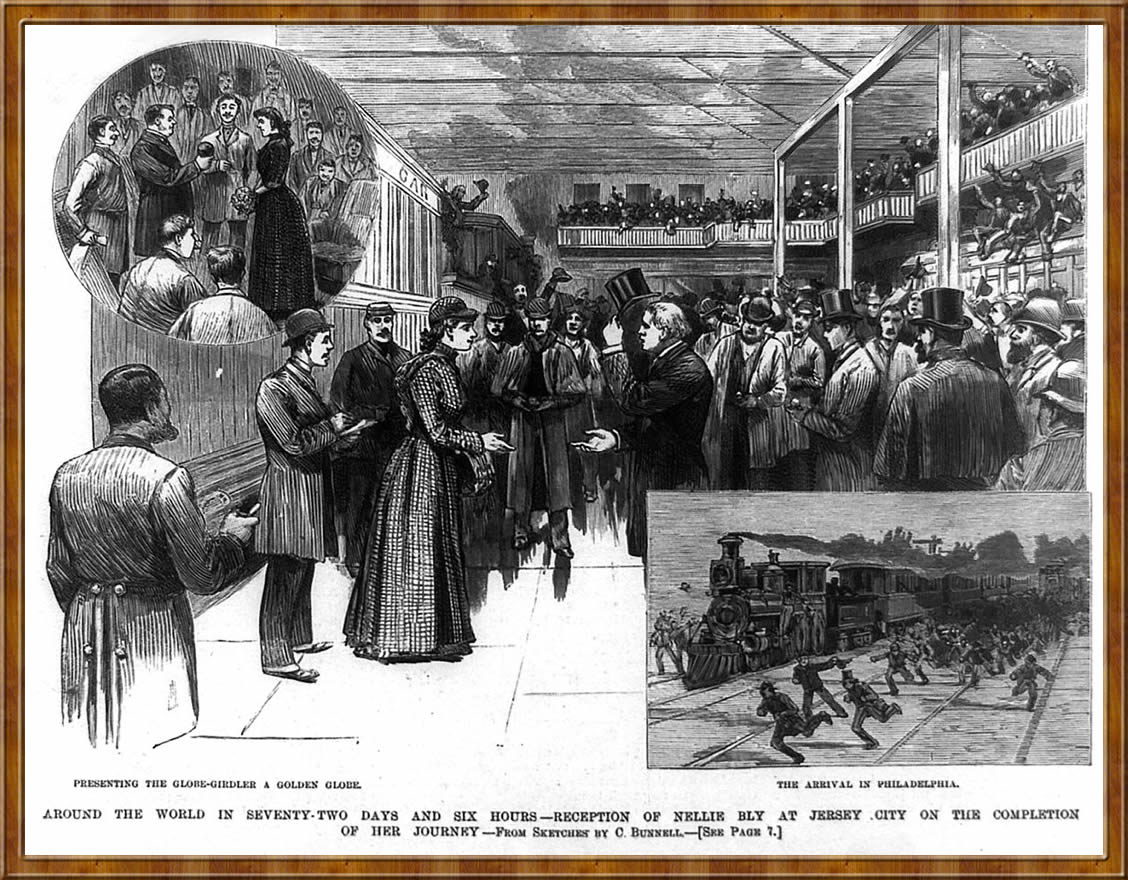

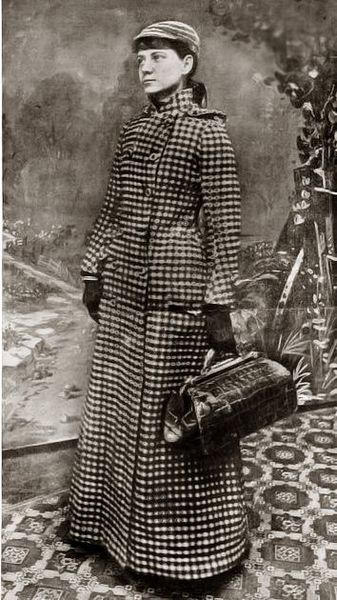

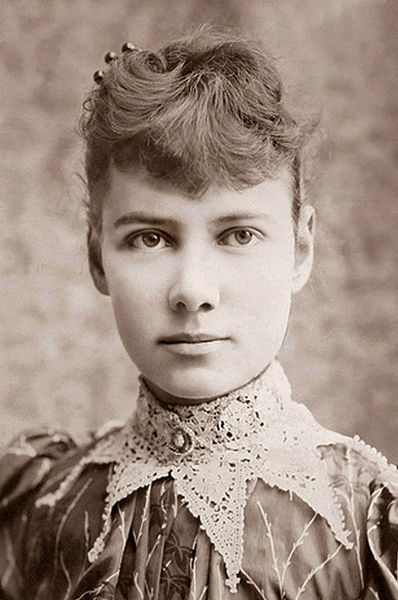

Eighteen-year-old Elizabeth Cochrane was living in Pittsburgh when the local newspaper published an article titled “What Girls are Good For” (having babies and keeping house was the answer, according to the article). The article displeased Elizabeth enough that she wrote an anonymous rebuttal, which in turned so impressed the paper’s editor that he ran an ad, asking the writer to identify herself. When Elizabeth contacted him, he hired her on the spot. It was customary at the time for female reporters to use pen names, so the editor gave her one that he took from a Stephen Foster song. It was the name under which she would become famous—Nellie Bly. Bly’s passion was investigative reporting, but the paper usually assigned her to more “feminine” subjects—such as theater and fashion. After writing a controversial series of articles exposing the working conditions of female factory workers, and after again being relegated to reporting on society functions and women’s hobbies, at age 21 Bly left for Mexico on a dangerous and unprecedented (for a woman) assignment to report of the conditions of the working-class people there. After her reporting got her in trouble with the local authorities, she fled the country and later published her dispatches into a popular book. At age 23, having established a reputation as a daring and provocative reporter, Bly was hired by Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World and there she began the undercover project that made her famous. In order to investigate the conditions inside New York’s “Women’s Lunatic Asylum,” Bly took on a fake identity, checked into a women’s boarding house, and faked insanity—so convincingly that she soon found herself committed to the asylum. The report she published of her ten days there was a sensation and led to important reforms in the treatment of the mentally ill. The following year Bly undertook her most sensational assignment yet: a solo trip around the world inspired by Jules Verne’s "Around the World in 80 Days". With only two days’ notice, Bly set out on November 14, 1889, carrying a travel bag with her toiletries and a change of underwear, and her purse tied around her neck. Pulitzer’s competitor, the New York Cosmopolitan, immediately sent out one of its reporters—Elizabeth Bisland—to race Bly, traveling in the opposite direction. As Pulitzer had hoped, the stunt was a publicity bonanza, as readers eagerly followed news on Bly’s journey and the paper sponsoring a contest for readers to guess the exact time of Bly’s return (with the correct guess winning an expense-paid trip to Europe). Seventy-two days later, Bly made her triumphant return (four and half days ahead of Bisland), having circumnavigated the globe, traveling alone almost the entire time. It was the fastest any human had ever made the journey. Nellie Bly was an international celebrity. At age 31 Bly married industrialist Robert Seaman, a 73-year-old millionaire, leaving behind her journalism career and her pen name. As Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman she helped run the family business. She patented two inventions during her time as an industrialist, but business was not her really in her skillset and under her leadership the company went bankrupt. When World War I broke out, she returned to journalism, becoming one of the first women reporters to work in an active war zone. Nellie Bly’s remarkable life ended on January 27, 1922 when she died of pneumonia in New York at age 57. |

|

|

|

|