| The Moving Story of Eyam Village |

RETURN |

| |

|

|

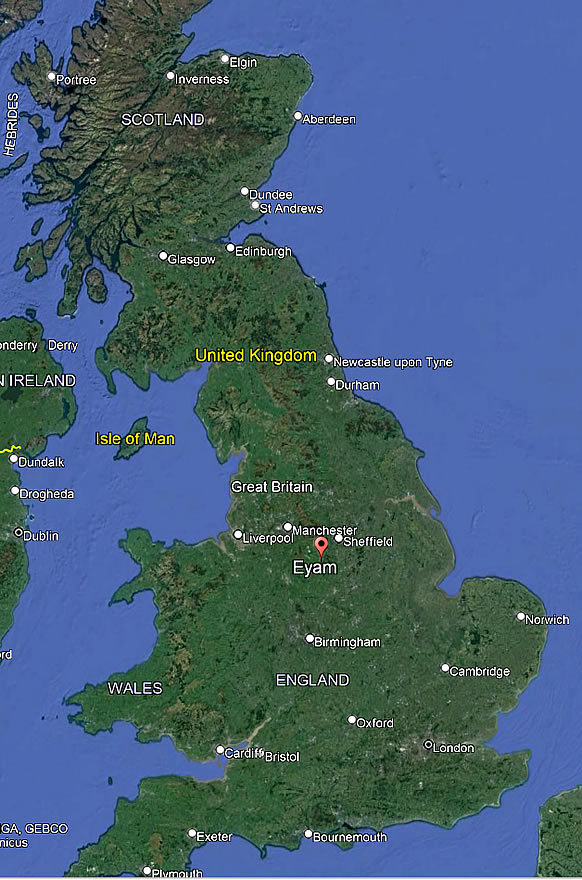

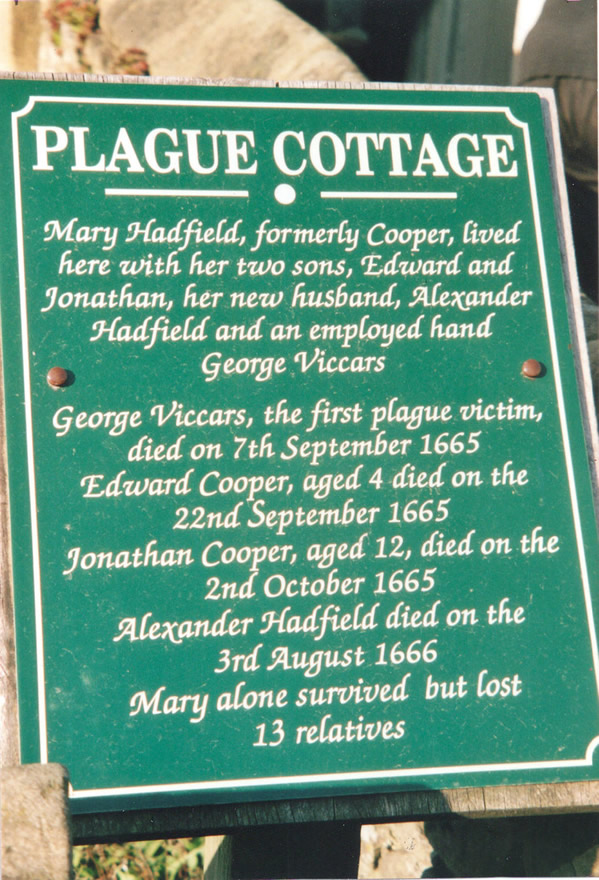

In September 1665 a collection of patterns was sent to the local tailor of Eyam, Derbyshire. His assistant dried the wet bundle in front of a hearth. In this way, it is believed, the plague spread rapidly through the village as the heat activated the plague carrying fleas from disease ridden London. Bubonic plague, its symptoms and dire consequences were well known and dreaded. The unpopular, distrusted rector William Mompesson wanted to quarantine the village to prevent the spread to neighbouring villages and was willing to support the people in every way, even at the cost of his life. He turned for help to the previous rector, Thomas Stanley who lived on the edge of the village and whom the villagers respected. Stanley was a supporter of Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans at a time when it was widely politically unpopular to do so, but he provided essential cooperation.

The Earl of Devonshire at nearby Chatsworth agreed to send all necessities to the villagers if they agreed to quarantine. Despite their fears and doubts, they agreed. Heavy stones were placed around the village. No one could travel out or in beyond that point. Food was left at the village edge and money was cleaned in vinegar to pay for it.

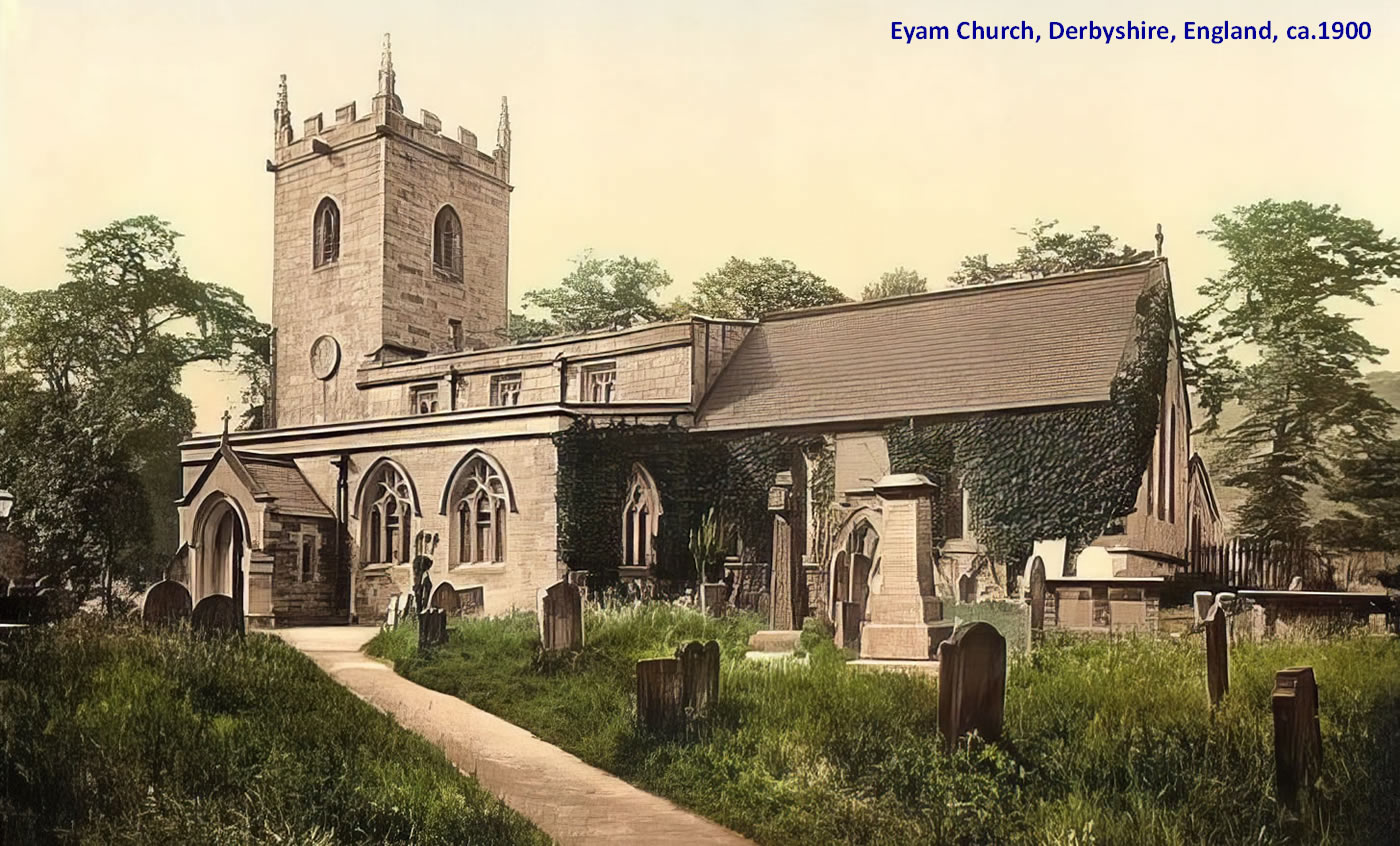

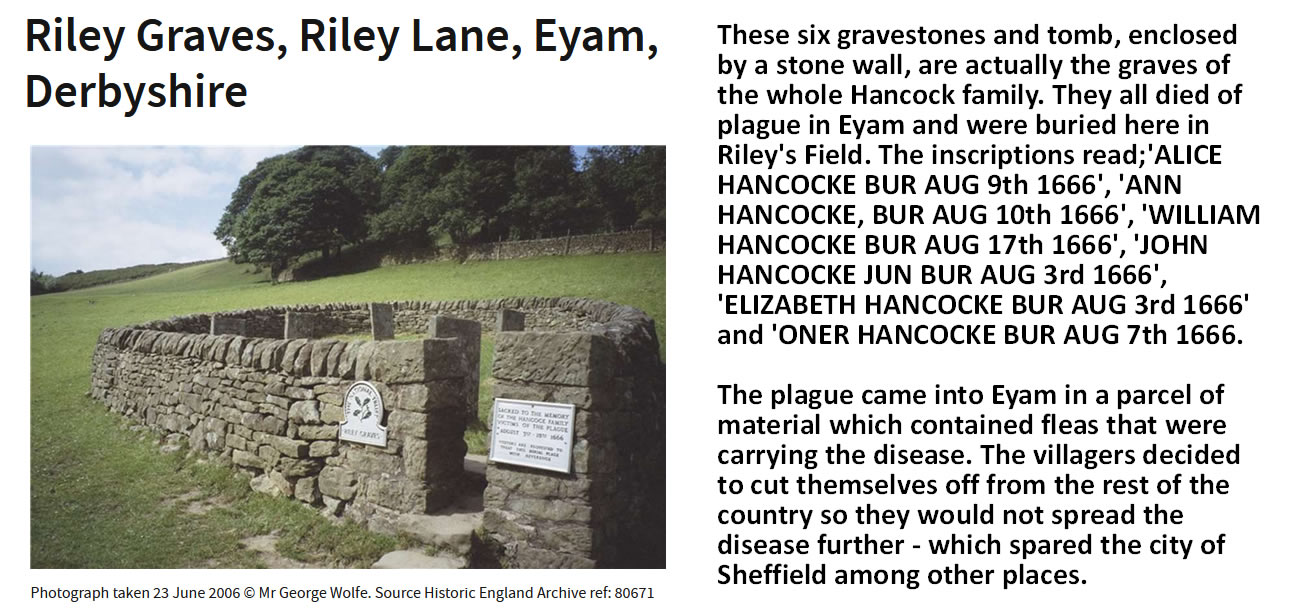

The results were predictably devastating. In August 1665, a very hot summer made the fleas more active and encouraged the spread of the plague to the point that the death rate was six a day. Elizabeth Hancock buried six children and her husband over a period of eight days near the farm. The graveyard had been filled. Those from a nearby village watched her, too frightened to assist.

William Mompesson’s faithful wife Catherine, who supported him through this terrifying experience, caught the disease and died aged twenty-seven on 22 August. By November the plague was over. Thirty-six percent of the population of Eyam had died but the neighbouring areas were saved.

In 1669 when Mompesson went to a Nottinghamshire village he had to live in a hut away from the centre for some time because of the fear that he might have brought contamination from Eyam. He paid a terrible price for his principled stand.

PS: Survival among those affected appeared random, as many who remained alive had close contact with those who died but never caught the disease. For example, Elizabeth Hancock was uninfected despite burying six children and her husband in eight days. The graves are known as the Riley graves after the farm where they lived. The unofficial village gravedigger, Marshall Howe, also survived, despite handling many infected bodies. Sadly, his wife and two-year-old child did get infected and die. |