“I was humiliated, my fear turned into anger,” she recalled. “I remember saying to myself, "I don’t know who they are or where they are, but I’ll find the people who are fighting this, and I’ll join them. ”

It took her two years. After contracting tuberculosis while studying midwifery she was sent to a sanatorium in Grenoble. Another patient introduced her to his Resistance network when they returned to Paris. Madeleine Riffaud took her nom de guerre, Rainer, from the German poet Rilke, whose Duino Elegies she had read while being treated.

"What kept me going was saying to myself: I am not a victim. I am a résistante. Hundreds of young women like me were involved,” she recalled. “We were the messengers, the intelligence-gatherers, the repairers of the web. When men fell or were captured, we got the news through, pulled the nets tight again. We carried documents, leaflets, sometimes arms. We walked miles; bikes were too precious, and the Métro was too dangerous.” For the next three weeks she was tortured by being whipped, electrocuted and half-drowned, yet she denied being a member of a Resistance network. She was scheduled to be shot on August 5. In her cell, she wrote poems: “Those who will kill me/ Do not kill them in turn/ Tonight my heart is nothing but love.”

As D-Day approached, networks such as hers were short of arms. She would approach policemen in the street to coax or threaten them into giving her their pistols. Shortly before her 20th birthday, a comrade was killed after being recognised by a German soldier whose life he had recently spared. Madeleine Riffaud also learned of the massacre of 643 people by the SS at Oradour-sur-Glane. She knew the village well as she had spent holidays in the area.

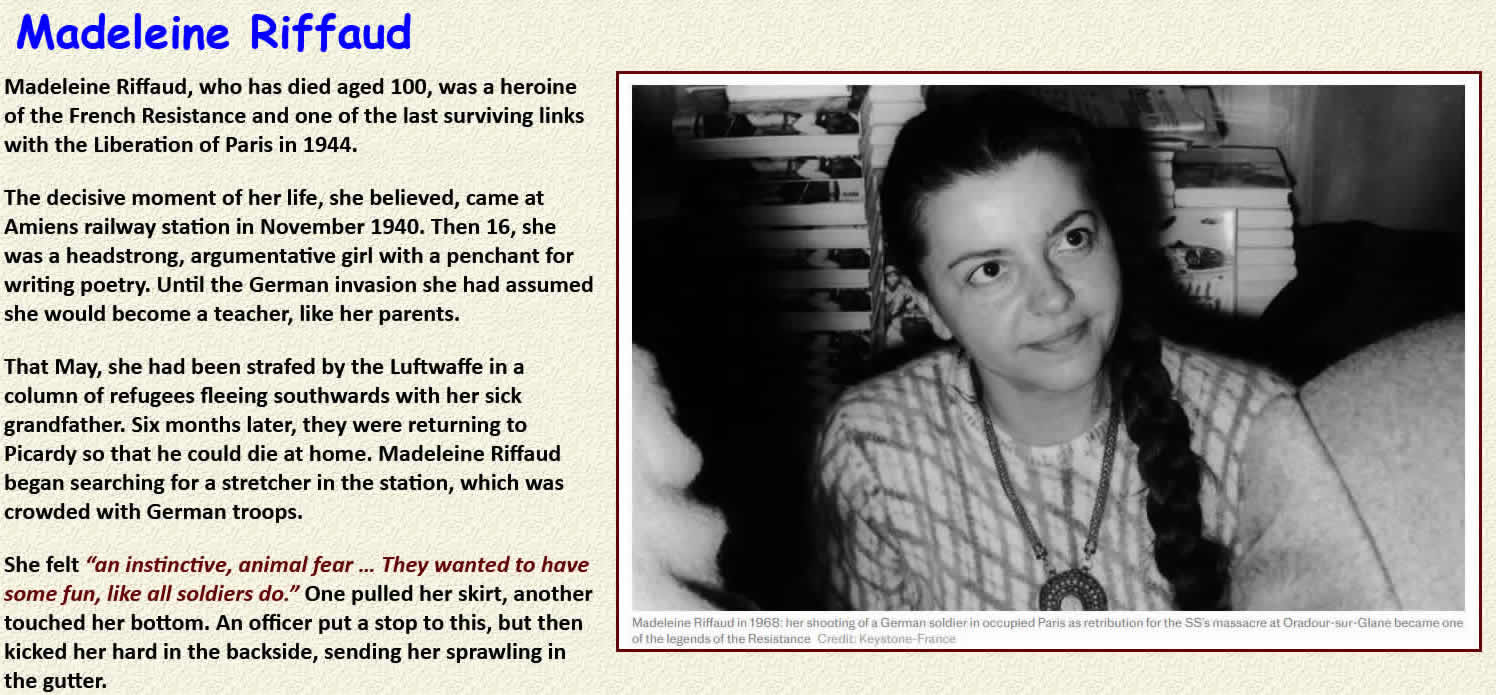

Vowing vengeance, on the evening of July 23 1944 she cycled along the Left Bank. At the end of Rue de Solférino, near the Musée d’Orsay, a German soldier was looking across the Seine to the Tuileries gardens. Madeleine Riffaud braked, planted her feet on the ground and shot him twice in the head. “He fell like a sack of wheat,” she wrote later.

“I was very calm, very pure .. … Maybe he was a good guy. But this ..… Well, it’s war.” The head of the Versailles Milice, the collaborationist police, was passing. He knocked Madeleine Riffaud off her bicycle with his car and handcuffed her. She was taken to the Gestapo prison in Rue des Saussaies. Catching a glimpse of herself in a mirror, she thought: “I am going to die.”

A few minutes before her execution, she was reprieved when a policeman recognised the gun she had used as the one taken from him by partisans. Madeleine Riffaud was tortured for another 10 days for her contacts. She was made to watch prisoners being disfigured and emasculated.

A teenager she knew had his arms and legs broken in front of her. “Don’t you like children?” her interrogator asked. “What kept me going was saying to myself: I am not a victim. I am a résistante.” On August 15 she was put on a train to Ravensbrück concentration camp, jumped off it, but was recaptured. She was finally freed in an exchange of prisoners four days later.

With the Allies advancing on Paris, she went straight back to fighting with the Free Forces of the Interior, in the rank of aspirant (lieutenant). On her 20th birthday she was ordered to take four men and stop a train carrying troops and arms. Firing from a bridge over the track, they forced the engine to halt, and eventually 80 Wehrmacht soldiers surrendered to her.

Paris’s German commander, Dietrich von Choltitz, capitulated on August 25. Madeleine Riffaud had spent the day fighting in the Place de la République, assaulting the SS barracks. “We were fighting floor by floor, dropping grenades through the windows.But you cannot understand how wonderful it was to fight finally as free men and women, to battle in the daylight, under our own names, with our real identities, with everyone out there, all of Paris to support us, happy, joyful and united.”

|