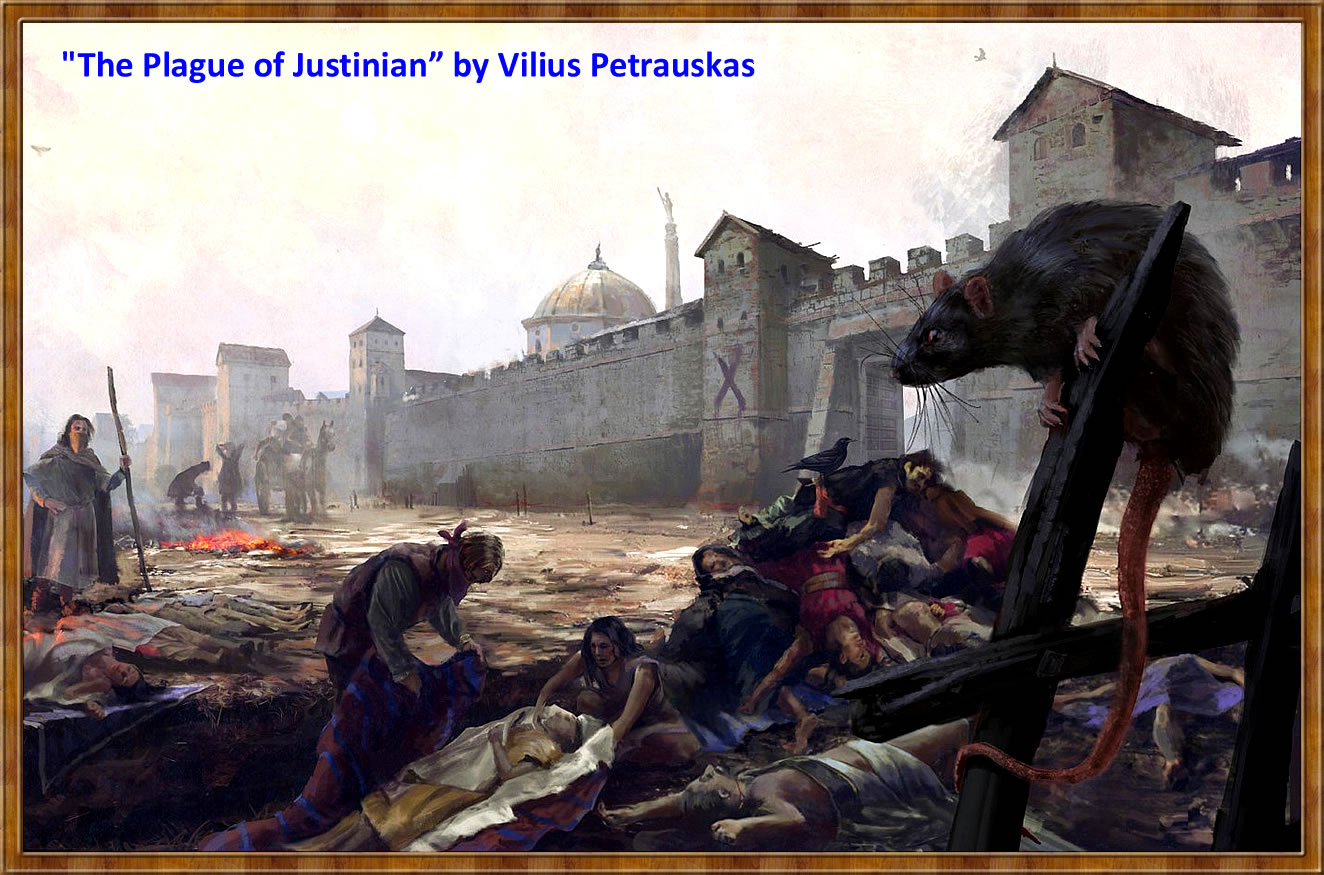

In the 6th century A.D., the course of history was changed by microscopic bacterium within fleas traveling on the backs of rats. The bacterium, Yersinia pestis, originated in central Asia and made its way to the trade routes of the Mediterranean, and from there into North Africa and Europe. When the infected fleas bit humans, they transmitted to them the bacterium. Easily treated with antibiotics today, that knowledge and technology did not exist in the 6th century. Infected humans developed fevers, severe pain, swollen lymph nodes, and mental breakdown. Death usually came quickly, but painfully. Although it is difficult to quantify the number of deaths, estimates are that the plague may have killed 25% to 40% of the population of the eastern Mediterranean. Because the plague arrived during the reign of Emperor Justinian (and because Justinian himself contracted it), it was known as and is remembered today as the “Plague of Justinian.” But we now know that it was the bubonic plague, which would return periodically to ravage Europe for centuries. Aside from the catastrophic personal human suffering it caused, the effects of the plague literally changed the course of an empire. From 541 A.D. until about 549, the Plague of Justinian wreaked havoc on the Byzantine Empire, depopulating it and crippling its finances. At the time the plague hit, Justinian seemed to be on the verge of recapturing the western Mediterranean lands and thus re-uniting the western and eastern Roman empires and churches. It was likely because of the effects of the plague that he was unable to do so, thus preventing the emergence of a greater Byzantium and thus enabling the eventual dominance of the Empire and Church based in Rome. The plague-weakened empire also allowed the Lombards to seize and hold northern Italy and enabled the Goths to strengthen and expand their presence on the frontiers. |

|