Rosalind Franklin was uncompromising with strong opinions and no fear to share them. But she also loved to have fun, spending time with friends at small dinners in the evenings or going on hikes or bike rides through the mountains on weekends. Friends said she liked to tease and had a mischievous wit.

Rosalind was born in 1920 in London, into a wealthy banking family. As a child, she hated dolls, hated pretend games. She was logical, literal, always seeking facts and reasons. But as the only daughter amongst three brothers for the first ten years of her life, she also wanted to be viewed as tough. She’d ignore pain, illness, once even walking blocks to a hospital with a needle stuck in her knee.

It was in school as a teenager that Rosalind fell in love with science, chemistry and physics in particular. At fifteen she decided to become a scientist. She set her sights on going to Cambridge University, to which she was admitted. But her father, who didn’t believe in a university education for women, refused to pay for her to attend. An aunt, the sister of Rosalind’s father volunteered to pay for Rosalind, as did Rosalind’s mother. With three women now against his decision, Rosalind’s father backed down and agreed to pay for her university education. After college, Rosalind took a job at the British Coal Utilization Research Association in South London. This was during WWII, so to get to work she’d have to ride her bike through bomb raids. She never complained, but she was scared.

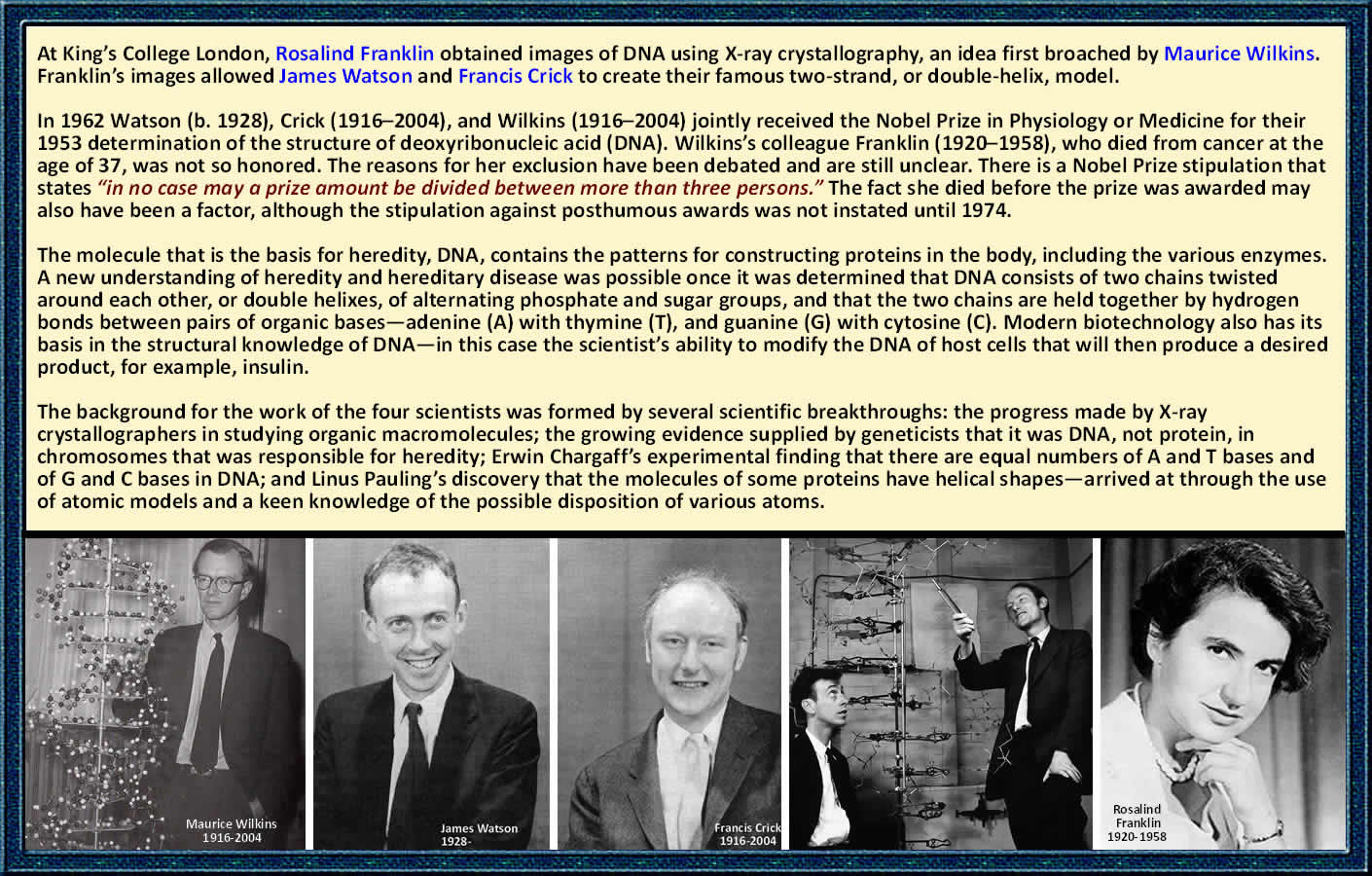

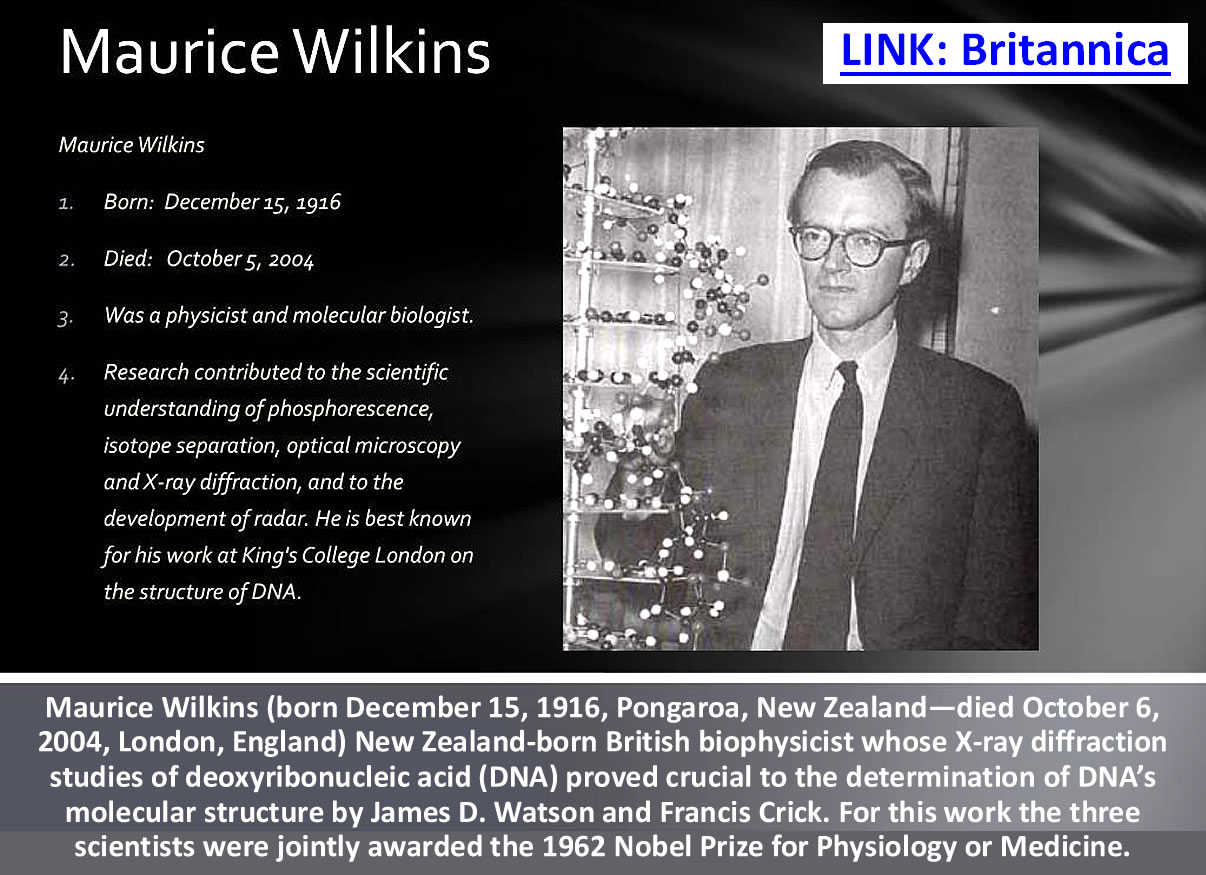

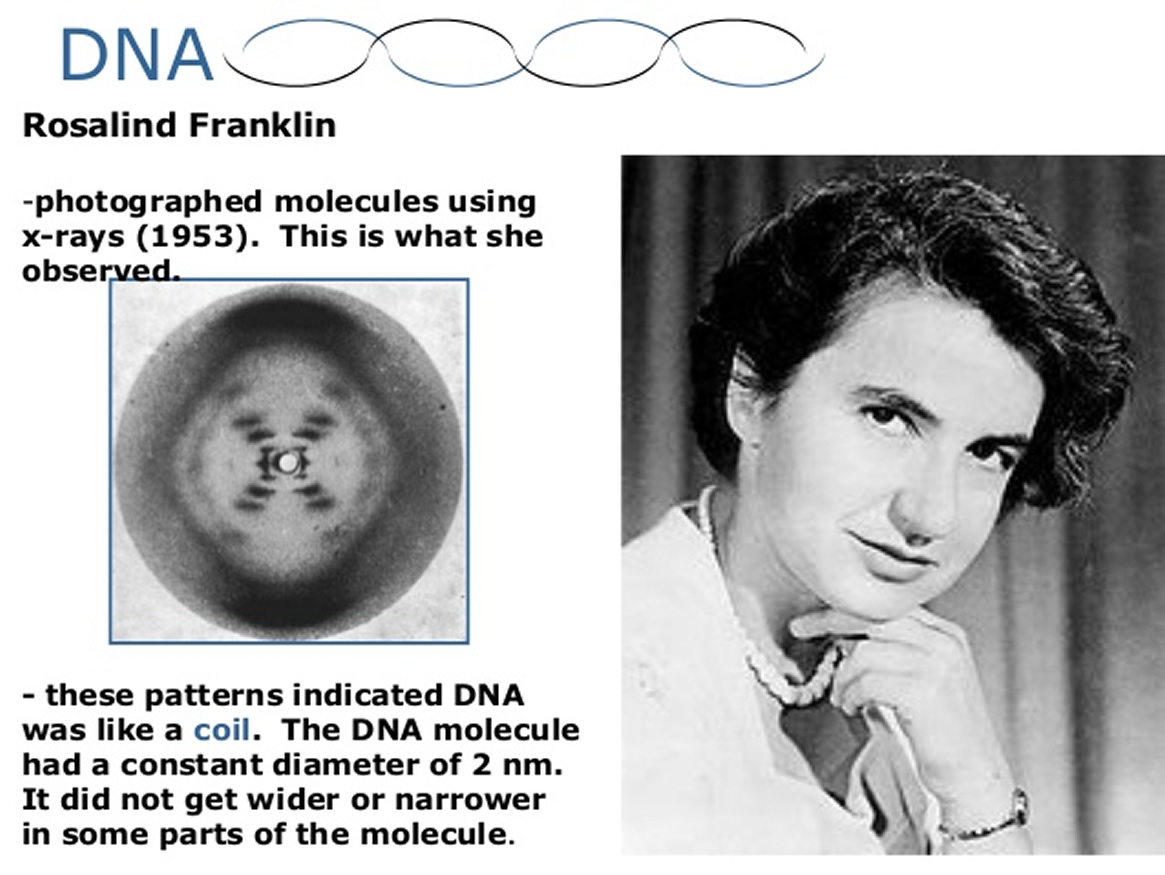

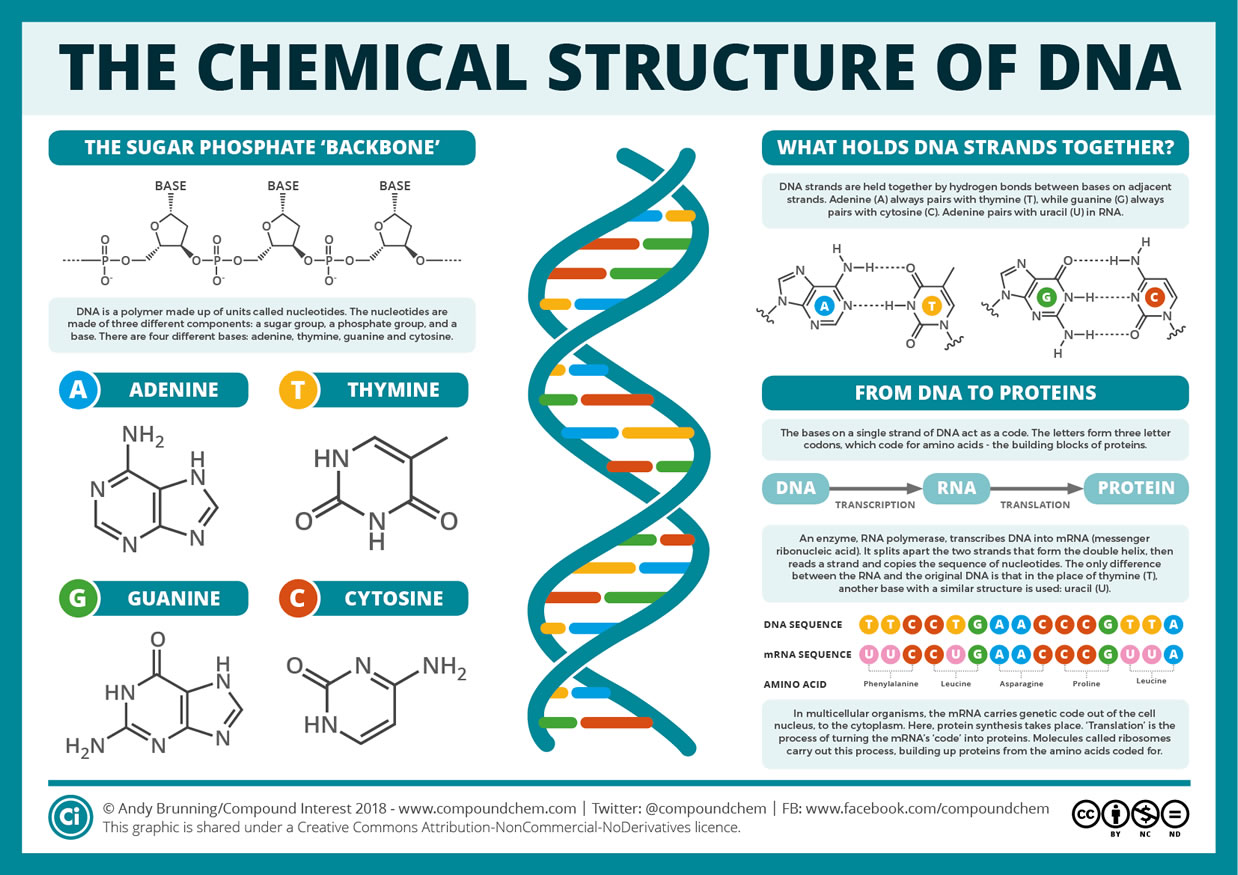

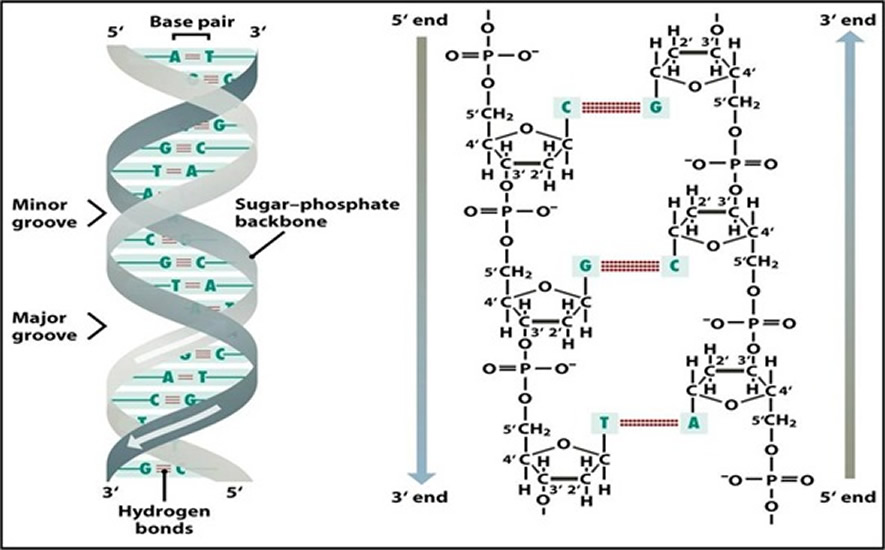

Her commitment to work pushed Rosalind through the fears. And it was in her work that she found much success. She published five papers, which are still cited today, dozens of articles. Her research changed the way scientists understood coal and similar structures. And her work earned her a PHD. She was 26 years old at the time and already an expert in her field. It was also in this work where Rosalind learned that she needed to understand X-ray technology, so that she could better understand physical matter, the matter from which the universe is made. She studied, became an expert, and then because of her expertise was offered a position at Cambridge to help analyze X-ray photographs of DNA molecules.

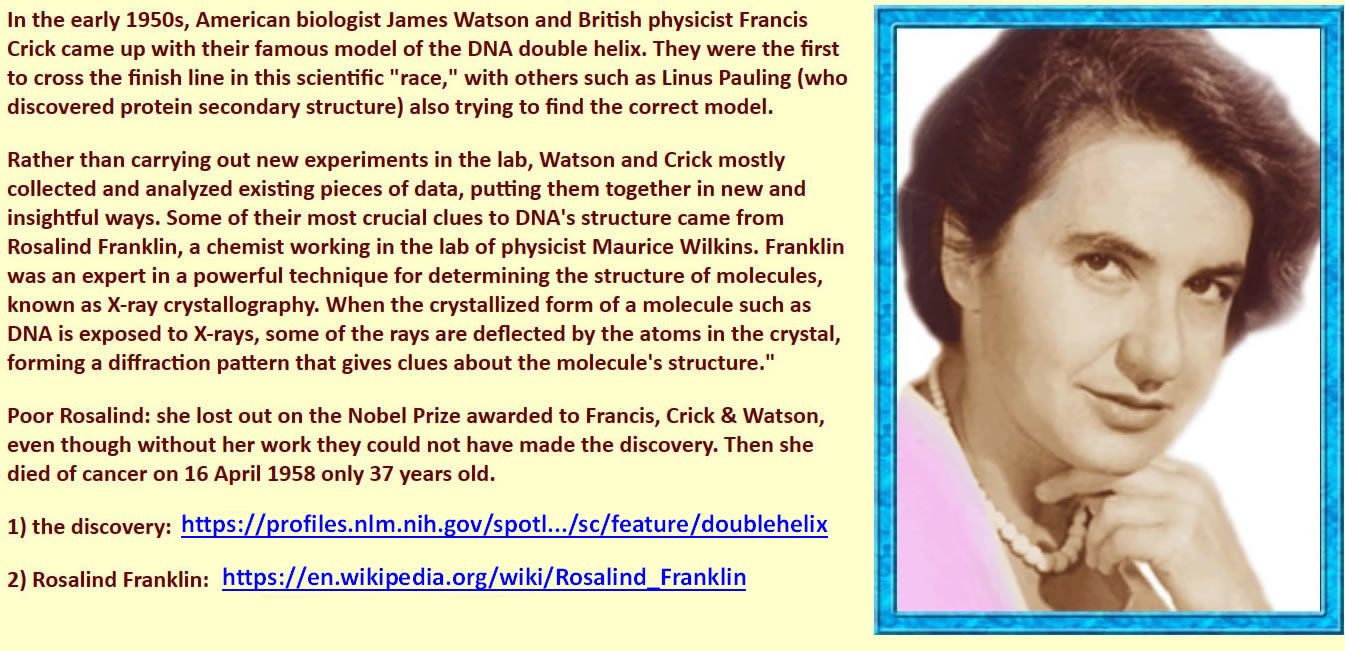

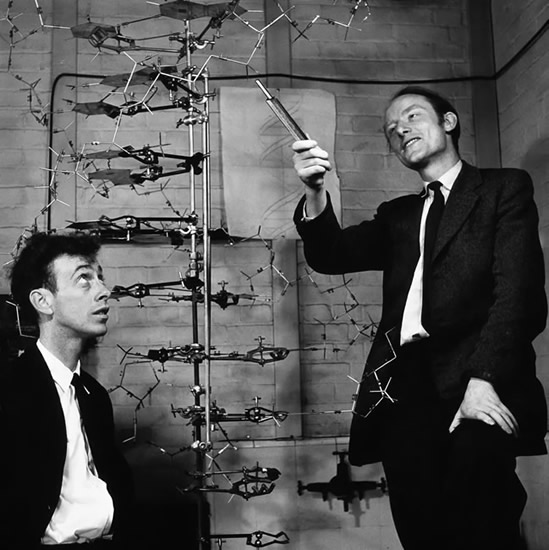

Focusing on determining the molecular structure of DNA, she took X-ray photographs that were considered the most beautiful of the time. And just as in her previous roles, she made critical discoveries, including the double helix structure. Her work helped build an understanding of DNA. But because of gender issues of the time, Rosalind received little credit for her work. The research she helped shape would earn a number of men a Nobel Prize, and they did little to credit her for the valuable research she did.

Rosalind dedicated her life to science. She never married. Even her love of children was set aside for science, as she couldn’t imagine the thought of her children raised by nannies while she worked. Rosalind Franklin had her life cut short when she passed away from ovarian cancer at only 37 years old.

|